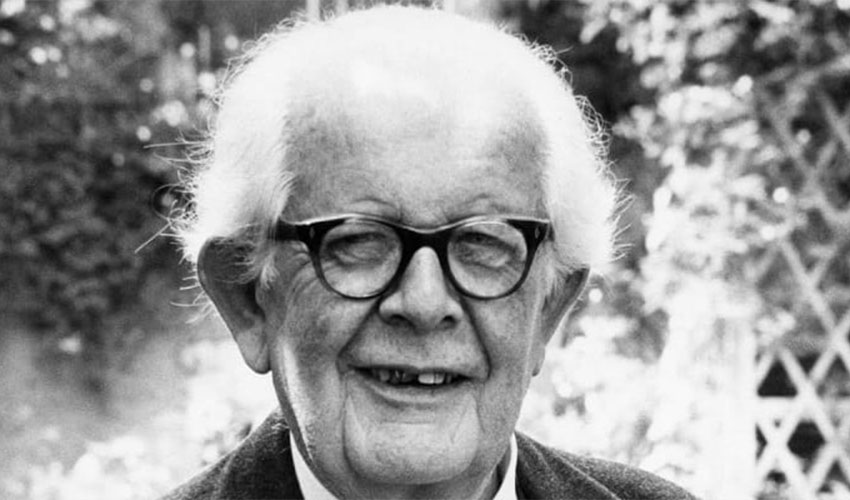

Jean Piaget, a Swiss psychologist born in 1896, stands as one of the most influential figures in the field of developmental psychology. His groundbreaking work on cognitive development transformed our understanding of how children learn, think, and perceive the world around them.

Jean Piaget’s pioneering work continues to inspire researchers, educators, as well as parents. He elucidated the mechanisms of cognitive growth and the stages of intellectual development. Piaget has provided invaluable insights into the nature of human learning and the unfolding of the human mind.

His early life was marked by a keen interest in biology and philosophy which laid the foundation for his later work in psychology. He was particularly interested in how knowledge is acquired and understood, leading him to develop a deep fascination with child development and learning processes.

Some psychological theories and concepts by Piaget in the developmental psychology realm are as follows:

The Theory of Cognitive Development

Through careful observation and analysis, Piaget identified common patterns of development and proposed universal stages of cognitive development that unfold in a predictable sequence across cultures and contexts.

Central to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development is the concept of constructivism – the idea that children actively construct their understanding of the world through interaction with their environment. According to Piaget, children progress through four stages of cognitive development: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational, each characterized by distinct ways of thinking and understanding.

Sensorimotor Stage (Birth to 2 Years): During this stage, infants explore the world through their sensory perceptions and motor activities. Key developments include the understanding of object permanence (the realization that objects continue to exist even when out of sight) and the development of basic motor skills.

Preoperational Stage (2 to 7 Years): In this stage, children begin to use symbols and language to represent objects and concepts. However, their thinking is still egocentric, meaning they struggle to consider other people’s perspectives. They exhibit animism (attributing human-like qualities to inanimate objects) and engage in magical thinking.

Concrete Operational Stage (7 to 11 Years): During this stage, children become more capable of logical thought, but it is still tied to concrete, tangible situations. They begin to understand conservation (the understanding that the quantity of a substance remains the same despite changes in its shape or arrangement) and demonstrate improved mathematical and logical abilities.

Formal Operational Stage (11 Years and Older): This stage is characterized by the development of abstract and hypothetical thinking. Individuals can think logically about abstract concepts and engage in hypothetical reasoning. They can understand complex problems and think about multiple variables simultaneously.

The Role of Schema

Piaget proposed that children’s cognitive development is driven by the processes of assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation involves interpreting new information in terms of existing mental structures or schemas, while accommodation requires modifying existing schemas to incorporate new information that cannot be assimilated. Through the dynamic interplay of assimilation and accommodation, children gradually develop more sophisticated cognitive abilities and conceptual understanding.

Example to understand Assimilation: Imagine a child who has a schema for birds based on seeing and interacting with pet birds, which are usually small and can fly. If the child encounters a penguin at the zoo, they might initially assimilate the penguin into their existing bird schema by thinking of it as a “funny-looking bird that doesn’t fly.” In this case, the child is using their existing knowledge of birds to understand and categorize the new information about the penguin.

Example of Accommodation: If the child encounters an ostrich, a large flightless bird, they may realize that their existing bird schema is not sufficient to explain the ostrich. To accommodate this new information, the child may modify their bird schema to include both flying and flightless birds. The child is adjusting their understanding (accommodating) to incorporate the new and diverse information about different types of birds.

Egocentrism and theory of mind

Piaget’s research on egocentrism in young children highlighted their tendency to perceive the world from their own perspective and struggle to understand the viewpoints of others. This concept laid the foundation for later research on theory of mind, which explores how children develop an understanding of other people’s thoughts, beliefs, and intentions. Piaget’s work on egocentrism contributed to our understanding of social cognition and interpersonal relationships in childhood.

In one of Piaget’s classic experiments, known as the “three-mountain task,” children were asked to choose a picture that represented the view of a doll placed at a different position around a model of three mountains. The child and the doll were positioned at different locations relative to the mountains.

Imagine a scenario where there are three mountains – A, B, and C – arranged in a row. A child is sitting on one side of the row and a doll is positioned on the opposite side. Each mountain has a distinct feature, such as a cross, a snowcap, or a house.

The child is asked to choose a picture that represents the doll’s perspective. Due to egocentrism, the child often selects the picture that reflects their own view, not recognizing that the doll has a different line of sight and, therefore, a different perspective of the mountains.

This experiment illustrates the child’s difficulty in grasping that others may have different perceptions or knowledge about the same situation. The child’s egocentrism leads them to assume that others see the world exactly as they do. Over time, as children progress through Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, they gradually overcome egocentrism and develop the ability to consider different viewpoints.

Object Permanence

One of Piaget’s most famous discoveries is the concept of object permanence, which refers to the understanding that objects continue to exist even when they are no longer visible. Through his observations of infants, Piaget identified object permanence as a key milestone in cognitive development, marking the transition from the sensorimotor stage to the preoperational stage. This insight has profound implications for understanding how infants perceive and interact with their environment.

Peek-a-Boo Game: The classic game of peek-a-boo is a simple yet effective way to observe the development of object permanence in infants. In the early months of life, infants typically lack a fully developed sense of object permanence.

- Infant (Before Object Permanence): When playing peek-a-boo with a very young infant, if you cover your face with your hands or a cloth, the infant may react as though your face has disappeared. They may show surprise or interest when you reveal your face again.

- Infant (Developing Object Permanence): As the infant develops a better sense of object permanence, typically around 8 to 12 months of age, they start to understand that you are still there even when they can’t see your face. This is when peek-a-boo becomes a more interactive and enjoyable game for them.

- Infant (Object Permanence Acquired): Once the concept of object permanence is firmly established, the infant anticipates your return during the hiding phase of peek-a-boo. They may even initiate the game by covering their own face or pulling a cloth over their head, understanding that you are still present even when temporarily hidden.

Piaget’s research methods were highly experimental, involving detailed observations of children’s behaviour and thought processes in naturalistic and structured settings.